(Alumina Ceramic Produced by Wintrustek)

Alumina is a more frequent name for aluminum oxide (Al2O3). It is a durable technical ceramic with an outstanding combination of mechanical and electrical characteristics. It is suitable for a wide variety of industrial applications.

Core Advantages:

1. Extremely high hardness:

2. Excellent insulation properties:

3. High temperature and corrosion resistance:

4. Good mechanical strength:

Manufacturing Process: From Powder to Hard Ceramic

Manufacturing a high-quality alumina ceramic product involves complex physical and chemical changes:

Powder Preparation: Alumina powder is mixed with additives (such as sintering aids).

Forming Process: Dry pressing, isostatic pressing, injection molding, or tape casting are selected depending on the required shape.

Sintering: The material is fired in a high-temperature furnace at 1600°C to 1800°C, causing the powder particles to bond into a dense crystalline structure.

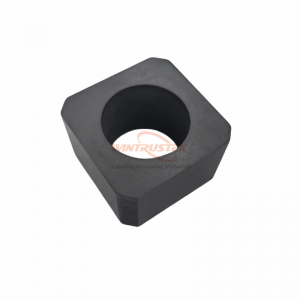

Finishing: Due to its extremely high hardness, finishing after sintering usually requires the use of diamond tools or grinding wheels.

This article focuses on several mainstream forming processes:

1. Dry Pressing

This is the most commonly used method in industrial production, especially suitable for mass production of simple shapes (such as sheets, rings, and washers).

Principle: Powder containing a binder is placed in a metal mold and subjected to unidirectional or bidirectional pressure using a press.

Advantages: Simple operation, high efficiency, precise green body dimensions, and easily controllable sintering shrinkage.

Limitations: Difficult to manufacture complex-shaped parts; due to frictional forces, the density of large parts may be uneven.

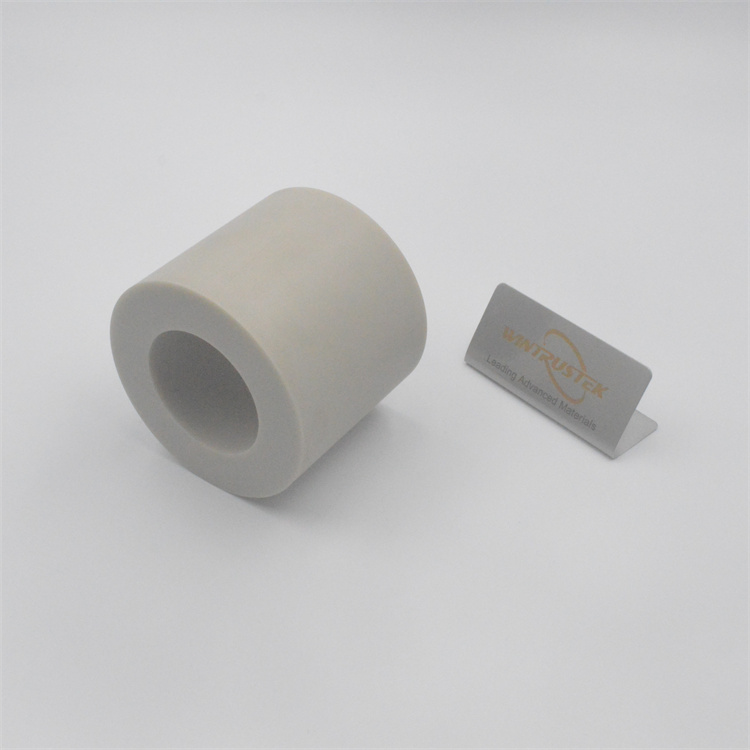

2. Isostatic Pressing

For high-performance parts requiring high density and uniformity, isostatic pressing is the preferred method.

Principle: The powder is sealed in an elastic mold (usually a rubber bag) and placed in a high-pressure vessel, using a liquid as the pressure-transmitting medium.

Core Advantages: The pressure is applied uniformly to the powder from all directions, resulting in highly consistent density throughout the green body and minimal deformation after sintering.

Applications: Commonly used in the manufacture of large ceramic tubes, spheres, or precision ceramic bearings.

3. Tape Casting

If you see ultra-thin ceramic substrates (such as the circuit boards in mobile phones), they are most likely produced by tape casting.

Principle: Powder is mixed with a solvent, dispersant, and binder to form a "slurry," which is then spread onto a conveyor belt using a doctor blade to form a thin film. The film is then dried and peeled off.

Advantages: Capable of manufacturing ultra-thin ceramic sheets with thicknesses between 10 μm and 1 mm.

Applications: Thick-film circuit substrates, multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCC).

4. Injection Molding

This technique, borrowed from the plastics industry, is used to manufacture parts with extremely complex geometries.

Principle: Alumina powder is mixed with a large amount of organic binder (up to over 40%), heated, and injected into a precision mold, then cooled and solidified.

Challenges: The "debinding" process (removing organic matter) before sintering is very lengthy and critical; improper handling can easily lead to cracking.

Applications: Ceramic precision parts, medical device components.

5. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

This is a cutting-edge technology in recent years that completely breaks the limitations imposed by molds on shape.

Main methods include: Stereolithography (SLA) or paste extrusion.

Advantages: No molds are required, making it suitable for developing prototypes or manufacturing ceramics with extremely complex internal structures (such as biomimetic skeletons and microfluidic chips).